[Revised for concision, May 2, 2010]

On June 4, 1780, British Lieutenant-General Henry Clinton wrote to George Germain, Secretary of State for the Colonies, to describe the situation in South Carolina. Clinton had turned over command in the South to Lieutenant-General Charles Cornwallis, and was preparing to return to the main British base of operations at New York. Clinton cheerfully reported that:

"With the greatest pleasure I further report to your lordship that the inhabitants from every quarter repair to the detachments of the army and to this garrison to declare their allegiance to the King and to offer their services in arms in support of his government. In many instances they have brought prisoners their former oppressors or leaders, and I may venture to assert that there are few men in South Carolina who are not either our prisoners or in arms with us."

Clinton was not alone in this opinion. Others writing to Germain at this time expressed a similar view.

On June 9, Loyalist James Simpson wrote to say that:

“the gentlemen in the country seem unanimously inclined to a restoration of the King’s government, whereas in town [Charleston] there are still some who associate in small parties and stimulate each other to continue in the rebellious principles which they have nurtured for some time past, and there is no doubt but that if they dared it would break out into practice; but they are very few, and I trust nothing that can happen will prevent the establishment of His Majesty’s authority and government which I am confident is eagerly wish for by four-fifths of the people.”

On June 10, the Crown-appointed (and exiled) Governor of North Carolina, Josiah Martin, wrote that:

“I have the great satisfaction to acquaint your lordship that this province is in all appearance subsiding fast into a state of peace and tranquility under the auspices of Lord Cornwallis whose wise and prudent measures I think cannot fail to confirm and secure it ours if they are not contravened. His lordship is pursuing the only plan of justice and policy that I have yet known conjoined with military operation in the course of the American war, and if the future measures of government relative to this people are founded upon the same just and sound principles of determination I think I may venture to affirm that Britain will again hold empire here."

As described previously, American accounts also indicate that submission to the Crown was widespread. Nevertheless, at the very moment when the British appeared on the verge of complete triumph, the seeds were being sown for their eventual defeat in the South. I will not attempt an exhaustive account of how British decisions at this period contributed to their defeat, but some likely contributing factors are listed below.

1. The British were slow to effect the reestablishment of Royal authority in South Carolina. Simpson complained to Germain that:

“I am to remain here for some time in order to contribute my assistance to establish and carry into execution a temporary civil police for the government of the country which must otherwise fall into anarchy and confusion, even if no persons were to remain in the province who are so infected with rebellious principles… I must consider it a misfortune that at a time when so much assistance is wanted there is not one of the King’s servants belonging to this province upon the spot except myself, and even my stay is precarious…”

2. Although the British demanded the allegiance of South Carolinians, they did very little to earn it. Many of the people that expressed support for the Crown did so out of precaution and not because of a change of heart. From a 21st-Century vantage point, one can argue that a hearts-and-minds campaign should have been launched, that high-ranking officers should have been sent into the Backcountry settlements to talk to the leaders about their fears and grievances and attempt some kind of accommodation. In any event, this did not occur.

3. British efforts to subdue the state were not uniform. Clinton's inclination was to be lenient with the people of South Carolina: his

June 3 proclamation released the militia that had borne arms against him from their paroles so long as they supported the Crown. This proclamation struck some British officials as ill-considered, and they felt free to go their own way. Martin warned that:

“if… in the spirit of concession and indulgence, innocence and guilt are confounded by undistinguished favour and lenity, and the means are unemployed which only have been found effectual to cure rebellion in all ages and countries, your lordship may depend the result will be nothing better than an unsound pacification, a shortlived truce to be soon followed by hostility more combined, compacted and confirmed.”

In other words, Martin was concerned with incentives; he wanted to ensure that those that were loyal to the Crown would be recognized and rewarded, whereas those that had not would be effectively dissuaded from rebellion.

Others favored the ruthless application of force to terrorize the population into submission (most notorious were Captains William Cunningham and Christian Huck).

Whatever benefit there was in any one of these strategies was undermined by the concurrent use of other strategies.

4. The British military response to unrest was inadequate.

Previously, I suggested that Cornwallis' plan to establish a network of (chiefly) Provincial-manned outposts in support of a new, Loyalist militia could have been central to a winning British strategy in the South. The British had few men relative to the territory they had to control. It was necessary for them to either spread themselves thin in an effort to control the countryside, or cede it, without a fight, to the Americans.

Once the American militia in the Backcountry became active and showed that it could dominate fights against their Loyalist counterparts [see Note 1], it was incumbent on the British to develop an effective response. However, the British were hampered by difficulties. The British might have embedded experienced officers in the ranks of the Loyalist militia, but they had few spare officers. Alternatively, the British might have developed a powerful, mobile reserve that could be sent to hot spots, but they had a shortage of horses and forage.

Notes:

1. It is unclear whether the Loyalists or Whigs could count more supporters in June of 1780. Perhaps more important than an advantage in numbers was the Americans' advantage in military experience. In a painstaking analysis of the battle of Williamson's Plantation, Michael C. Scoggins identified 142 participants on the "American" side. Of these, at least 33 (23%) had prior service as Continentals in either the 3rd or 6th South Carolina regiments. The defeat of Loyalists in early June at Alexander’s Old Field and Mobley's Meeting House presaged a future in which the American militia would frequently dominate their Loyalist counterparts.

Sources:

Transcriptions of letters by Clinton, Simpson, and Martin in K. G. Davies. (1978).

Documents of the American Revolution 1770-1783 (Colonial Office Series). Volume XVIII: Transcripts 1780. Irish University Press.

The website,

The Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, hosted by the University of North Carolina, includes a transcription of the

Letter from Josiah Martin to George Germain, June 10, 1780.

Michael C. Scoggins. (2005).

The Day It Rained Militia: Huck's Defeat and the Revolution in the South Carolina Backcountry, May-July 1780. (link to amazon.com).

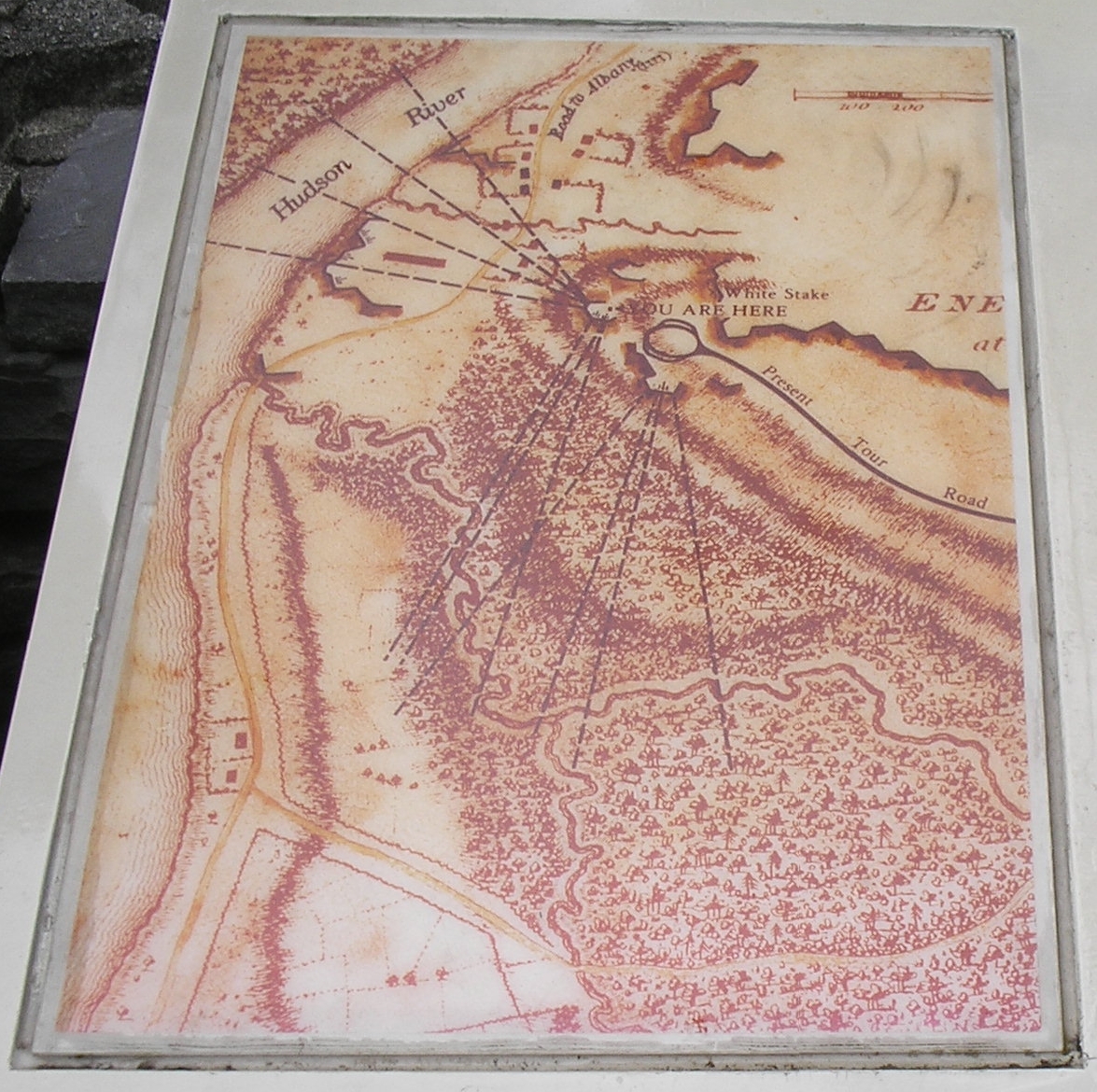

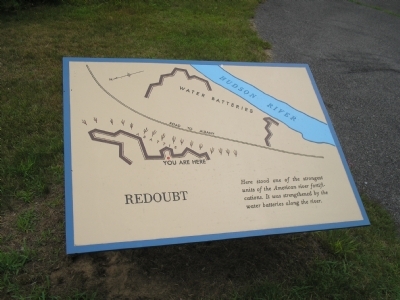

Contested Carolina, June 6-20, 1780 (click to enlarge). The dark line bisecting the map is a part of the boundary between North and South Carolina. Map section from Henry Mouzon et al.'s 1775 An accurate map of North and South Carolina...

Contested Carolina, June 6-20, 1780 (click to enlarge). The dark line bisecting the map is a part of the boundary between North and South Carolina. Map section from Henry Mouzon et al.'s 1775 An accurate map of North and South Carolina...